The Pakistan government has banned the film that will be its Oscars contender after pressure from hardline Islamic groups who called its depiction of a love affair between a man and a trans woman “repugnant” and “highly objectionable”.

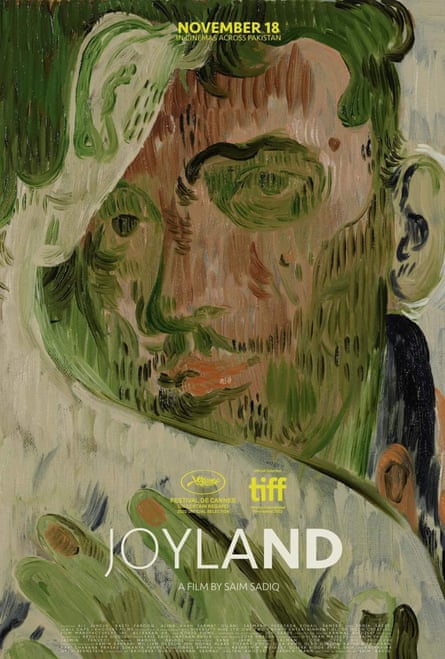

Joyland, directed by Saim Sadiq, had been submitted as Pakistan’s official entry for best international feature film at the Oscars and was due for domestic release this week.

The film tells the story of a Haider, a young married man from a middle-class family in Lahore, who joins an erotic dance theatre and falls in love with Biba, a transgender performer.

The film had garnered glowing praise on the festival circuit for its tender and critical depiction of Pakistan’s patriarchal society. It was the first Pakistani feature to be an official selection at the Cannes film festival, where it was awarded the prestigious jury prize.

Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani Nobel prize-winner who joined the project as an executive director, hailed it as “such a moment of joy … The themes that are touched upon in this movie resonate with people all around the world.”

Joyland had been given the green light by Pakistan government’s censor board, but it backtracked after a campaign began against the film, led by the country’s religious hardliners and powerful Islamic rightwing parties, including Jamaat-e-Islami.

Senator Mushtaq Ahmed Khan, from the Islamic movement Jamaat-e-Islam, had accused the film of promoting homosexuality, which remains illegal in Pakistan, and being “against Pakistani values”.

In an order given by the country’s ministry of information and broadcasting over the the weekend, it said it had received written complaints about Joyland, alleging that the film did not “conform with the social values and moral standards of our society and is clearly repugnant to the norms of decency and morality”.

Joyland has now been uncertified for all Pakistan cinemas, meaning its release is banned in the country. The ban jeopardises the film’s chance at the Oscars as it is a condition of entry that the film must be shown in its home country.

In a statement, Sadiq called the ban a “grave injustice” and said he would be challenging the decision.

“This sudden u-turn by the Pakistan ministry of information and broadcasting is absolutely unconstitutional and illegal,” said Sadiq, accusing the ministry of caving to “pressure from a few extremist factions”.

Sarwat Gilani, an actor in the film, spoke out against what she alleged was a paid smear campaign by “some malicious people who have not even seen the film”.

“Shameful that a Pakistani film made by 200 Pakistanis over six years, that got standing ovations from Toronto to Cairo to Cannes, is being hindered in its own country,” said Gilani. “Don’t take away this moment of pride and joy from our people.”

In previous interviews, Sadiq has spoken about his concerns releasing the film in Pakistan.

Speaking to Variety, he said he hoped the film would offer a fresh, non-western perspective on trans issues. “This film does introduce a new leaf in terms of the conversation around that, because it’s just refreshing to see a very empowered trans character who happens to be brown and Muslim and in a country like Pakistan,” he said.

Pakistan, which is a strict Islamic republic, has a long history of banning film and cultural content that challenges religious or societal norms. In March, censors banned the Pakistani film I’ll Meet You There for allegedly portraying a negative view of Muslims. The Da Vinci Code is among the Hollywood films that have been given bans by government censors.

The Pakistani author Fatima Bhutto called the ban “senseless”. “Pakistan is teeming with artists, filmmakers, writers and has a cultural richness and more importantly bravery that the world admires,” Bhutto said in a tweet. “A smart state would celebrate and promote this, not silence and threaten it.”